AGAIN: Repetition, Obsession and Meditation

Lannan Foundation

313 Read Street, Santa Fe, NM

Review for The Magazine by Richard Tobin

June 2013

HERACLITUS GOT IT RIGHT, UNLESS WE GOT HIM WRONG

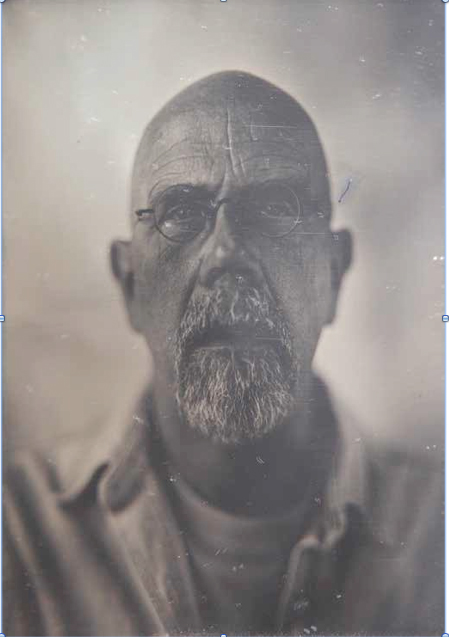

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait, daguerreotype, 5½” x 4¼ ”, 1999

A few extant Greek fragments transmit his auricular notion of change (rendered in equally cryptic English) to say that you can’t step in the same stream twice, what with its ever- changing flow. His point was not that everything changes—hence, nothing repeats—but that change itself is not a foil against constancy, or permanence—change is, in fact, a condition for it. The metamorphosis of lepidoptera from caterpillars to butterflies is change; the transition from moth to flame is not. With change understood as a force for continuity, repetition is a fundamental expression of it. And obsession is the ongoing search for that abiding truth which reveals itself

through repetition. Once revealed, its import is engaged and absorbed in meditation.

The philosopher’s insight could serve as the premise for AGAIN: Repetition, Obsession and Meditation (on view through June 16), the current group exhibition of works from the Lannan Collection that exemplify one or more of these related themes as “key elements to the artist’s process, sometimes quite obvious in the resulting art work, sometimes not.” Repetition is rendered as pure iteration in Buzz Spector’s altered book Portrait of Dorian Gray, (1989) and in Cassandra C. Jones’ Track and Field prints; it is realized in the evolving progression of Susan York’s solid graphite bars and of Pard Morrison’s Mutation series.

And any viewers familiar with the repetitive process of an Agnes Martin (on view here) and an Eva Hesse would concur that iteration underscores the crossover nature of obsession and meditation. AGAIN makes that case with an engaging clarity and without distracting from the strength and appeal of the art itself.

A constant focus—fixation— on the bird motif leads Jean-Luc Mylayne to include one in each of his chromogenic prints. Renate Aller’s ten- year record of atmospheric seascapes photographed from a single, fixed vantage point invites contemplation. Olafur Eliasson’s The Lighthouse Series is an homage to Bernd and Hilla Becher’s typologies dating from circa, 1959, groupings of documentary-style, single-image gelatin silver prints of industrial structures assembled in suites within a grid format under a common “type”. Recalling the Becher 1972 Typologies of Water Towers, Eliasson’s grid of five rows of photographic color prints depicts twenty lighthouses. The documentary stamp of the nondescript structures is enriched by the distinct personalities that they assume within the grid. The juxtaposed variation in design, surrounding landscape, and cultural context underscores their differences while it tacitly asserts a common structural unity and shared pensive tilt.

groupings of documentary-style, single-image gelatin silver prints of industrial structures assembled in suites within a grid format under a common “type”. The documentary stamp of the nondescript structures is enriched by the distinct personalities that they assume within the grid. The juxtaposed variation in design, surrounding landscape, and cultural context underscores their differences while it tacitly asserts a common structural unity and shared pensive tilt.

The repetitive device at work in such architectural typology can be traced in turn to earlier serial art—recall Monet’s series of haystacks and cathedral facades—and of course to nature itself. In AGAIN, Jorge Pardo’s yellow-and-green monoprints of eucalyptus leaves explore a basic botany that resonates in the red-yellow-blue geometric shapes of Pard Morrison’s enamel-on-acrylic Mutation, in which the facets of Cubist constructions unfold, like the flattened sides of milk cartons, to assume new identities.

Sol Lewitt’s two etchings are variants of the tenth print of an edition of fifty whose

. The key to Lewitt’s obsessive tack can be found in his phrase “drawn at random,” which allows each etching its unique visual pattern within a larger identity whose continuity is assured by that very variation. Lewitt’s “straight lines” titles mimic the genetic markers that scientists use in DNA sequencing.

Sol Lewitt’s genome mapping is matched by Agnes Martin’s method of penciling horizontal and vertical fields, as seen in several lithographs (12” x 12”) on vellum depicting her signature grid compositions. Arguably the most understated work in AGAIN, Martin’s modest lithographs convey the monumental tranquility of her typical six-foot and subsequent five-foot grid squares. And the subtle lyric quality in Martin’s sober grids resonates in the rigorous striations of Stuart Arends’ Stanza dell’ Amore 24, whose pattern of parallel vertical ridges and grooves belies the geometric probity of the piece with its melodic feel of a Renaissance lute.

The éminence grise of AGAIN is Self-Portrait (1999) by Chuck Close. Chosen to illustrate the theme of obsession (here, Close’s lifelong preoccupation with the portrait), its photographic medium of the daguerreotype offers an unwitting riff on AGAIN’s themes. Daguerreotype, involving a unique direct print on a silvered copper plate, is, almost by definition, an antonym for repetition. Yet with its equally furtive image that shifts from positive to negative, depending on the viewing angle and color of the reflected surface, Close has produced a self-portrait that appears to both vanish and reveal itself, affirming that the seeming randomness of change is essential to our enduring sense of continuity. Heraclitus got that right.